As the year draws to a close and award season kicks in, one title that’s been making the rounds is Mob Psycho 100, the highly anticipated third season and conclusion to author One’s original work of the same title. With its impeccable animation quality, superb storytelling and beautiful ending, it’s already garnered quite a few anime of the year nominations, likely cementing its legacy as an all-time classic. Having followed the current simulcast, there is certainly a lot to celebrate as Mob and friends move into the next chapter of their lives while dealing with religious occults, an overgrown vegetable with a God-complex and Mob’s own conclusion as he settles into adulthood.

Folks, I’m not actually here to talk about Mob Psycho 100 III. Not yet at least.

Don’t get me wrong, I’d rather be talking about the show’s finer points in detail. The brilliant animation by Studio Bones, the blazing soundtrack of Kenji Kawai, the talented performances of Bang Zoom!’s English cast — is what I would be saying under normal circumstances, but 2022 was far from normal. Record high inflation, untimely deaths and the rise of entertainment monopolies, all factors the anime industry certainly wasn’t immune to.

This year saw the complete merger of former rivals Crunchyroll and Funimation, effectively making Sony — and by extension, Crunchyroll — the dominant stakeholder in anime distribution and streaming services. As the old saying goes, “with great power comes great responsibility,” an irony not lost on me given who currently owns the rights to Spider-Man. Yet time and time again, month after month saw new stories of how Sony’s plans to upend the anime market through aggressive expansion and takeovers is putting the industry’s future into further uncertainty.

For the casual observer, most will no doubt gloss over the fine print and simply be satisfied that most of their anime is now located under one roof. Others will look for answers elsewhere, hypothesizing what could have been or how we got to this point. Some might even accept the new status quo as they put up their hands, reach for a neutral position like “it doesn’t affect me,” “it can’t be helped” or “it could have been worse,” and call it a day. Regardless of your position, it’s easy to look at 2022 as the year where Sony finally collected all the Infinity Stones and snapped its fingers, taking the anime industry by force.

But that’s not the beginning of this story. Contrary to popular belief, Crunchyroll’s issues didn’t begin in 2022. It didn’t start after absorbing Funimation or being bought out by Sony the year prior. Nor that godawful period when Crunchyroll Originals were still around. Not even the 2010s as I reviewed my sources. It’s a tale that spans many years, going as far back as the company’s origins to its transition to legitimate business and several key changing points in ownership, priorities, and a few fumbles that persist to this very day.

I’ve been dying to tell this story for a while now, but seeing the final product, I can honestly say it was more work than I bargained for. However, if this story can educate, inform, and light a fire under you the same way it did for me while I was researching it, I’ll take my chances. After all, if you love the medium, I’m going to assume you care equally for the people and the process behind your favorite anime. If you’re a paid subscriber, I’ll also assume you’d be interested in knowing where your money is going. To be more specific, have things changed? In the years since its inception, have conditions improved at all? In the end, did Crunchyroll maintain its own ideals?

We’ve got a lot to cover, so let’s not waste any more time. This is the story of how a small underground web site became the largest anime conglomerate in the world, and the price it paid along the way.

The Early Years, Ellation (VRV), and Funimation Partnership

Founded in 2006, Crunchyroll began as a small anime piracy site founded by three college graduates with a shared passion for anime. Starting out as a web page “by fans, for fans,” users began to populate, socialize, and even “fansub” or subtitle unlicensed footage of anime. As the company began generating capital, a decision was made to go legit. Following the release of Naruto Shippuden on January 8th, 2009, the company pledged to halt and remove the distribution of unlicensed content as they explored a subscription model.

It was a bold gamble with vocal protests over the company “selling out” the community it had built, but one that cemented their future legacy as they rose to become one of the biggest anime streaming services on the planet, reaching 1 million paid subscribers in 2017 and over 20 million registered users worldwide. As one of the most influential anime distributors, it’s no surprise that many would hold the company in high regard having had a direct hand in popularizing and legitimizing anime in North America. Just as Funimation had become synonymous with English dubbing and home video releases, Crunchyroll would do much of the same with subbing and anime streaming.

But as the company accumulated wealth and influence, a gradual shift began to materialize, starting with a change in leadership. In a personal blog by journalist Lauren Orsini, she referenced the acquisition by Ellation, a new company focused on subscription-based services. Ellation, for those unfamiliar, is an umbrella company spun off Otter Media, which itself launched off of The Chernin Group when they purchased Crunchyroll in 2013. Long story short, Ellation now ran Crunchyroll, which would put the timeline around 2015–2016 where I began my investigation.

2016 would prove to be a fruitful year when Ellation launched VRV and announced a new partnership between Crunchyroll and Funimation to stream each other’s content and collaborate on some titles (dubs, video distribution, etc.). For a brief time, it proved to be a win-win scenario as both companies could prioritize what they know and fans had a surplus of choice, including the option to access both services through VRV if you lived in North America. Behind the scenes, however, a different story was unfolding as certain factors would prompt the partnership to end prematurely.

2018 — The End Is Nigh

On October 18th, 2018, Funimation and Crunchyroll announced that their partnership would expire later that year, marking the end of their joint venture as both companies looked for other opportunities. At the time, the news came abruptly with onlookers raising several questions, all of which can easily be boiled down to what I can charitably call “corporate politics.”

See, both companies were undergoing their own internal restructuring with Sony Picture Television acquiring Funimation the previous year and Crunchyroll being picked up along with Otter Media by AT&T. From an outsider’s perspective, it’s clear that both of the anime streamer’s parent companies viewed the other as potential competition, and in the years that followed, Sony and AT&T/Otter Media would claim their stake in the anime market.

Still, makes you wonder what could have been, doesn’t it? Apparently, so did then-president and CEO of Funimation Gen Fukunaga who recounted the days just before the companies failed to renegotiate a favorable deal:

“We did try to renew with [Crunchyroll], but there were some terms that they would not give on that we really had to have, to have a longer-term renewal with them,” Funimation President and CEO, Gen Fukunaga told Newsweek. “And they wouldn’t budge, and we couldn’t renew on those terms. So Sony had to make this tough decision: if they weren’t going to budge on those terms, then we just have to double down and decide if we’re going to go at it alone. And that’s what happened.”

Per that same interview, Newsweek elaborated further, noting the dispute centered on global expansion. As Sony wanted to expand Funimation worldwide, Crunchyroll’s existing mandates denied them the opportunity to stream in certain regions.

Now recall the original terms of the partnership. Both companies would agree to license and share a number of titles. Funimation would agree to dub and release titles on home video — two services Crunchyroll was severely lacking in its portfolio and would continue to delegate afterwards — while Crunchyroll could continue to stream subbed versions of said titles and offer the former a slot on their parent company’s VRV service. In other words, you could at the time theoretically subscribe to one service and be somewhat assured that most if not all the latest seasonal titles would be on there. The only decision would be whether you want subs, dubs, or both — Crunchyroll, Funimation, or VRV — and maybe a basic understanding of computer networks if you lived elsewhere.

But once Funimation came back to Crunchyroll to renew a longer deal with the intention of expanding their services globally — again, dubs, home video, streaming — the world’s largest streamer had other plans in mind.

“Now wait a minute Dark Aether! Why shouldn’t Crunchyroll protect its own interests? It’s just business as usual between rival companies. Survival of the fittest! Besides, didn’t Sony end up buying those guys anyways?”

An astute observation dear reader! Competition generally brings out the best because it requires competitors to continually innovate and expand to keep up with their growing consumer base. So before moving onto our next section, I’d like to direct your attention to Crunchyroll’s mission statement and keep this in mind as you read further down. Per usual, this will be a running theme:

2019 — Price Hikes: An Obligatory Discussion About the Crunchyroll App

With the conclusion of their agreement, 2019 would be the first major obstacle for Crunchyroll and Funimation as they renewed their focus on their services and user bases. With other streaming giants like Netflix and Amazon showing greater interest in the anime market, major companies redoubled their efforts through fierce bidding on the season’s hottest shows and presenting their case to earn your hard earn dollars! “Exclusive content, worldwide broadcasting, your golden ticket to a constant stream of anime for one low monthly price!”

For Crunchyroll, that all changed on March 22nd where the company began notifying users that their bill would be going up by 15%, marking the first time the company has made a notable price hike in over a decade. When asked by Kotaku if the company had plans to introduce new features to justify the price hike, Crunchyroll issued the following statement:

“Due to rising costs of content and infrastructure, now is the time to introduce new subscription pricing. This price increase will help us bring our community more of their favorite shows, allowing us to create even more experiences for them to connect with each other and through shared passion for anime.”

Looking through any forum, Reddit, or even your local college’s Wi-Fi network, it’s pretty much common knowledge that Crunchyroll’s native apps have had their fair share of issues over the years. But I’m not here to layout every single technical bug or reiterate on another story of “he said, she said” because it’s been done to death. Instead, I want to focus on what Crunchyroll has been doing in the time since. To that end, I’m highlighting three of the biggest core issues that overall have had an effect on the public’s perception of the company. Mind you, this is not an exhaustive list — only the three I felt are the most consistent issues frequently referenced.

A Lack of Innovation, Failure to Keep Up with Competitors and Maintain Industry Standards

For a lot of people — myself included — Crunchyroll and anime became almost interchangeable with the medium, offering both free and paid subscriptions at a time when anime was still a niche product. While there’s no denying that the company had a major influence in pushing anime into the mainstream, in the time since, other companies have caught on, investing heavily into their respective streaming services and taken a keen interest in outbidding each other for the streaming rights of various IP.

To that end, let’s start with Netflix. Arguably one of the pioneers of streaming as a concept — for better or worse — the company for a time was seen as the gold standard in how to design a user-friendly and painless streaming experience at the touch of a button. In August 2017, they introduced the world to the “Skip Intro” button, a concept so ingrained into the company’s brand that now it’s become almost industry standard with Disney Plus notably borrowing heavily when it launched its platform and Funimation test piloting the feature with a select number of series.

2022 hasn’t been the kindest year for the once popular streamer as they slashed through their own animation department and is currently rethinking its anime strategy. But years earlier, the company would enter a groundbreaking agreement that would play a key role in reopening the discussion for fair and equal treatment. In a move that would set a new precedent leading into today’s current labor discussions, Netflix would become one of the first to publicly sign an agreement with SAG-AFTRA that would pay actors a standardized rate among other benefits.

While there is debate that the company’s current business model of “binge-watching” and inconsistency with embracing simulcasts and simuldubs is detrimental to the engagement level of anime, at a time when companies have been cutting corners, abusing hype culture — more on that later — or not airing acquired content with no guarantee it’s coming in the near future, there is an argument to be made that a general, mainstream service like Netflix has the potential to draw audiences who don’t normally watch anime.

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, one of 2019’s runaway successes, shattered records near the end of its anime run, with Weekly Shonen Jump editor-in-chief Hiroyuki Nakano observing the shifting consumer interest from weekly simulcasts to binging following the series’ newfound popularity. While 2013’s The Devil is a Part-Timer! had its fans, its newfound cult status — particularly here in the west — arguably came after a lengthy run on Netflix right until its sequel announcement and subsequent exit off the streaming service in March of 2021. Regardless of your personal viewing preferences, there’s no denying that anime is more popular than ever before and the binge model is here to stay to some degree even as Netflix experiments with simulcasts.

But if I had to sum up the Netflix experience in one sentence from crashing on the couch to painfully deciding what I’m the mood for, it would be this — it simply works.

Once considered the second dominant player in the anime streaming wars and best known as the “dubbing company” to those in the west, Funimation’s history stretches back all the way to 1994, famously collaborating with a little-known franchise called Dragon Ball. Initially working behind the scenes to license and distribute titles commercially, the company would go on to play a major hand in fast-tracking the rise of “simuldubbing,” beginning in October 2014. 2016 would see them reenter the streaming wars with the launch and rebranding of their streaming services. Retitled as FunimationNow, the new service would see its fair share of ups and downs as their reputation and service infrastructure started to deteriorate entering the 2020s.

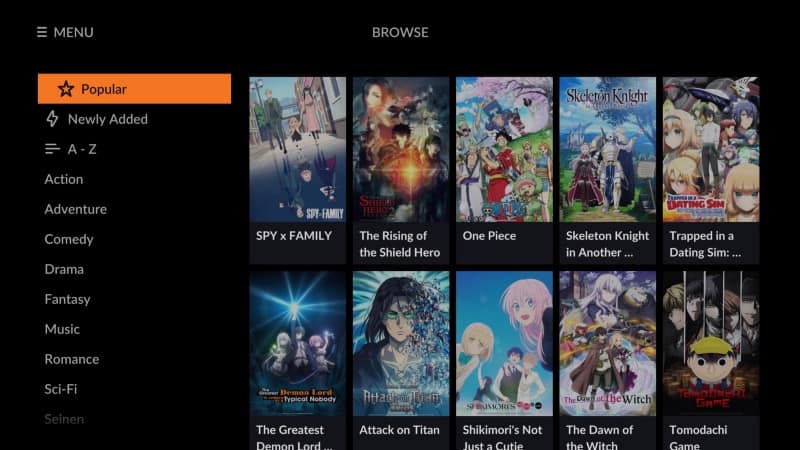

Under pressure and in the middle of a global pandemic, the company made one final push and did something out of left field — they listened. By 2020, work was already underway to redesign their apps which was officially unveiled following the release of the dedicated Nintendo Switch app later that year on December 14th, becoming the first dedicated anime app on the platform and the second subscription service to launch on Switch following Hulu. In 2021, a team of engineers would start rolling out the new version to all other platforms with the iOS version getting a notable touch up that following June. Featuring new filtering options, the ability to flip between dubs and subs on a switch and — most importantly — a simple method to check simuldubs either via the latest updates or what’s on the calendar, the redesign was remarkably improved.

So where does that leave Crunchyroll? In 2021, the company began a beta to redesign their website. In the interest of fairness, Crunchyroll did make one major addition I’ve not seen replicated elsewhere — the ability to manage, name and create personal lists called “Crunchylists”. It’s pretty useful if you’re sharing an account or watching multiple things and trying to keep mental notes on your backlog. Unfortunately, that’s where my positivity ends, because if we examine the fine print (note: the bold is their emphasis):

In reviewing this, I noticed a distinct lack of mentioning their other apps. Notably, the Crunchylists is missing in their console apps (PS4, Nintendo Switch). Also absent is any specifics on what’s actually changed in navigating between subbed and dubbed content. On other competitors, you simply flip a switch to alternate between languages. On Crunchyroll, you can’t even turn on subtitles/closed captioning for dubbed content, and that’s a major accessibility flag in my book. Worse still, some titles like the currently airing season 6 of My Hero Academia are straight up missing subtitles in the English dub, from the episode titles and other descriptors.

(Editor’s note: if your immediate thought is “why don’t you just flip to the subbed version,” see here.)

Even once you’ve found your content, you still need to manually navigate your preferred language which will differ slightly depending on the show. For most, languages are divided into “Seasons” and unceremoniously dumped into one lump sum. Then there are the odd exceptions with titles like My Hero Acadamia and Attack on Titan frustratingly separated into two separate blocks — one for regular Japanese broadcasting (subtitled) and one solely for English and all other languages (dubs). For being two of the most popular shows out there, it’s a weirdly exclusionary way to advertise “hey, we have dubs now!”

Next is the overall organization for updated shows. Across all apps, you can only view what’s been recently updated on the day of release, with new updates phasing out old ones. Miss a simulcast or two? “Sorry, but you can watch the most recent stuff here!” Want to know what shows are actually being simuldubbed this season or see when they go up without having to navigate to the blog? “Nope, but hey, have you heard about One Piece?”

Yes, as a matter-of-fact hypothetical talking anime mascot! And I would appreciate it if you would start uploading the latest simuld- “What’s that? Did you say One Piece Red? Good, here’s an unskippable pop up the next time you load the mobile app, plus a bunch of mobile games you’ll never download!” Okay, fine! Can I at least check my Crunchylists on my home consoles, my preferred apps when I watch on the couch?!

Putting aside the bugs and glitches from a work in progress, the biggest issue with the new app is that general sense of “corporate creep.” I don’t care what Joe Anime or what some Hollywood weeb is watching, I want to know why the hell my watchlist keeps flipping me over to episode 1 (subbed) after finishing a new episode! There’s a disturbing sense of promotional push where the app’s algorithm generally favors the most watched shows or the shows the company wants you check out. It doesn’t take an “anime expert” to realize when your recommendations are probably being curated by the guy who runs the company social media — or a really convincing AI! Because while the company continues to promote its most buzzworthy shows, you were probably too distracted to notice what it wasn’t promoting.

An Inconsistency with Simuldub Promoting

Now a free agent, Crunchyroll needed to look elsewhere and produce their own dubs in order to compete with its former partner. As part of this push and to alleviate growing concerns from fans, they announced that dubbed content would still continue to be added to the platform through various partner studios. Over the years, Crunchyroll would continue to churn out dubs for a select portion of shows with the intention of launching their own home video brand or enlist the help of existing companies to fill in those gaps.

“Crunchyroll has been heavily involved in the production of dubs for years with our partner studios at BangZoom, Studiopolis, Funimation, Ocean, and more. While our international audiences have enjoyed these efforts, we’ve remained more behind-the-scenes with our English dubs. Aside from the Crunchyroll logo on some home video releases, you may have not even known we were involved!”

With titles like Re:Zero − Starting Life in Another World, Mob Psycho 100, Bungo Stray Dogs, KonoSuba: God’s Blessing on This Wonderful World!, and Welcome to Demon School! Iruma-kun bolstering the library, things seemed to be headed in the right direction. Depending on what kind of reader you are and how in touch you’ve been with current events, chances are some of you are reading this section and asking yourself, “wait, Crunchyroll has dubs?!” If this is your first time being made of aware of it in the year of our lord 2022, you have my condolences.

Before continuing, let’s revisit the concept of brand. Crunchyroll as a brand started off as a place to catch the latest anime straight from Japan, often taking a hands-off approach and building itself as exactly that — subtitles and all. Now they wanted a piece of the English dub pie. To use an analogy, they were an Americanized sushi restaurant now trying their hand at selling burritos. How do you pull that off?

Well, for starters, you advertise the shit out of it and make the best damn burritos you can. While it’s safe to say there wasn’t really an issue with the latter producing some of the aforementioned titles above among others, including some personal favorites if we’re being honest, the former left a lot to be desired, starting with their social media presence. Browsing their three biggest platforms for fan engagement — their Twitter, YouTube pages before acquiring Funimation (rebranded as “Crunchyroll Dubs”), and official news blog — and activity between 2019 and 2021, a clear pattern emerges. Now, I shouldn’t have to spell it out, but if you were a casual viewer observing from the outside, well:

Any guesses where the majority of their marketing went towards? We’ll revisit that topic in 2019, but looking at the core issues outlined above — the lack of improvement and user support, the inability to integrate key features and standardize best business practices, and failure to prominently feature and promote their work unless it’s directly beneficial to the “brand,” it’s not a priority.

The Value of a Crunchyroll Subscription and Supporting the Industry(?)

Given what we’ve discussed above, you might be wondering where exactly your hard-earned dollars are going towards. Before closing off this section, let’s briefly review what you’re currently getting as of this writing.

From a purely quantitative measure, you have the largest anime streaming service with over 1000 shows at about (using the cheapest tier as a measure) $7.99 — or $95.88 annually. With the deemphasis of the free tier earlier this year, the ongoing migration of Funimation’s content and services, and new shows being advertised as an incentive to move out of the free tier, all eyes are on Crunchyroll to not only deliver on product, but also justify those aforementioned price hikes. With anime now bigger than ever and the money pouring in, in theory, this should lead to better quality, content, and experiences from the creator’s side to the user’s table, right?

Putting aside that my bill went from $60 to $100 in the transition from Funimation to Crunchyroll, here’s a brief rundown of my experience. At least 3–4 crashes on various devices (web browser seems to be the most stable), been repeatedly kicked off all of my primary devices at least once (if not more), and have had varying degrees of “success” browsing through dubs for several shows in what I can charitably call “organization.” Many of the articles I’ve written on this very site had images taken from my phone via the Funimation or VRV apps whenever possible, with only Netflix and Crunchyroll deploying the copyright enforcement police, forcing me to pull up my computer’s web browser for screenshots.

Of course, that’s just my experience, and I’m happy to put up with it if it means creators and people behind the scenes are treated and paid fairly — if that were the case. As news broke out over Mob Psycho 100 III’s recasting and people started vocally contemplating cancelling their subscriptions over social media, an image began to make the rounds when they got to the cancellation screen. Either a huge oversight on the company’s end or an open admission of their own negligence, it painted a grimmer reality of Crunchyroll’s priorities. And to further make their intentions clear, another price increase was announced for international territories later that month.

“Don’t miss out and help us continue running our side hustles like Crunchyroll Expo! Crunchyroll Awards! Crunchyroll Originals! Crunchyroll Games! Crunchyroll, AMIRITE?” For a company that bills itself as “the champion of art and culture of anime”, that’s a whole lot of Crunchyroll and not a whole lotta anime. Obviously, the goal of any business is to make money, but when you frequently talk about supporting the industry and continue to engage in activities that very clearly undermine the people you claim to represent, insult your customers and employees with poor workmanship and unethical practices, and actively portray yourselves as a guardian angel of the medium, there’s a four-letter word for this situation:

But I’m getting ahead of myself, because we haven’t even covered Crunchyroll’s biggest flop — and how they covered it up.

2020 — The Fall of Crunchyroll Originals

Up until now, I’ve telling this story chronologically, but for 2020, I figured I’d start at the end result first. On June 18, 2021, Anime News Network published an investigative report detailing the mismanagement and miscommunications involving various studios Crunchyroll had dealings with regards to their newly minted Crunchyroll Originals. It’s a lengthy and well-informed read that I encourage you to visit at your own leisure, but for our purposes, I’m going to focus on three major points — the inconsistent quality between projects, the broken communications and subsequent fallout from creators, and Crunchyroll’s marketing and prioritization.

First off, what is a Crunchyroll Original? Well, years earlier, with competitors vying for anime streaming rights and venturing into uncharted waters, someone at Crunchyroll took notice and wanted a method that would simultaneously ensure their competition wouldn’t call dibs first and continue to build their brand. It was right around this time where everyone wanted their own exclusives to call their own or at least be involved in their development — financially or creatively.

With the streaming wars heating up, the term “Original” or similar wording became ubiquitous to a company’s brand. Today, almost every major platform has some form of exclusive content, and while not all of them are inherently owned or created by said companies, the idea stuck around — or someone was watching way too much Stranger Things (looking at you Ubisoft)! In any case, Crunchyroll decided, “hey, we can do that too!” and began to coproduce anime through a number of studios and business ventures.

Before Crunchyroll Originals, this actually wasn’t the first time the company dipped their toes into coproduction. Their involvement can be traced back to 2015 with 19 different shows being released in 2017. Several other notable titles include Laid Back Camp, The Rising of the Shield Hero, and Odd Taxi, to name a few. If you’re asking why these aren’t considered Crunchyroll Originals, you can chalk that up to a combination of timing, marketing, and yes, “branding.” To avoid further confusion, you can see the official list of Crunchyroll Originals on the company’s site.

For the record, I do think there was good intentions with this initiative. A way to differentiate themselves by highlighting content and creators from around the globe, promoting new and diverse stories beyond typical anime and manga, and more content to justify that $100 annual renewal. But within a year, most of their Originals would crash and burn, two of the most critically panned anime would debut from it, and by the following year, the company would scale back, reserving the brand for a few odd Japanese titles and some leftover deals it so desperately wished it hadn’t signed off on.

Now that we’ve got the lengthy intro out of the way, let’s go over those three key points in detail:

A Lack of Quality Control

If there was one definitive issue with Crunchyroll Originals, it’s the consistently mixed results plaguing almost every production. I’ve covered this topic in detail across multiple shows which I’ve highlighted at the bottom of this page, but due to a lack of direction, pacing, and some cut corners in key areas, many of these shows would fail to make much of an impact in a year where anime production had already been severely undercut entering the 2020 pandemic. The ones that did would do so for reasons Crunchyroll didn’t anticipate or already knew they had a PR nightmare on their hands.

Taking a brief tour into the “Nine Circles of Anime Hell,” Giabate and EX-ARM proved to be the most disastrous of the lineup, playing host to several “Worst Anime of the Year” winners, scathing criticism and being the butt of many jokes online. Moving up the ladder, titles like FreakAngels, Onyx Equinox, and High Spice Guardian would all suffer from a combination of internal politics, creative differences, Crunchyroll’s lack of transparency and — in the case of FreakAngels — a real world controversy surrounding its author Warren Ellis, though that title did eventually release… for some reason.

Up next is the grab bag of shows. In/Spectre was a neat idea turned boring exposition dump that failed to materialize on the mystery angle. So I’m a Spider, So What? proved even a great actress can’t carry a yet another bog-standard isekai except with uglier CGI. Tonikawa… exists (even I know better than to provoke the rom-com mafia!). As for Dr. Ramune, did anyone who reads this site actually watch that show? I’ll wait. Not that it matters since it didn’t even rank in AniTAY’s Top Anime of 2021 out of a list of 67 shows the year it had finished.

Before we ascend further, you’ll notice I skipped over some notable titles — the webtoon adaptions and Adult Swim productions. My opinions on the manhwa trinity are well documented, so for this piece, I’m looking at them through a new angle as they relate to Crunchyroll’s marketing. For Adult Swim, however, we need to return to an earlier point to examine the second major flaw in Crunchyroll’s rollout.

Broken Promises, Communications, and Bridges

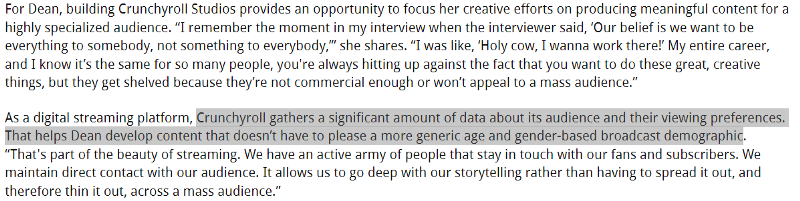

One of the key elements Crunchyroll Originals advertised was looking outside of Japan for inspiration. One such inspiration would lead the company to their home state of California where they would open up a brand-new studio in Burbank for the sole purpose of making anime right at home. Founded as Ellation Studios in 2018, they would later rebrand to Crunchyroll Studios Burbank with Margaret Dean at its head. “We’re really trying to build the studio that we’ve all been talking about as far as diversity and inclusion,” she would later remark on the studio’s focus.

Keeping in line with that studio focus on ethnically diverse stories and Crunchyroll’s promotional efforts to highlight the potential of their Originals, High Spice Guardian would be announced as their first joint venture. Originally scheduled for a 2019 release, it would later unceremoniously drop on October 2021 to divisive results. While the show’s legacy would largely become mired in a firestorm of angry rhetoric and online outrage over its LGBTQ+ and diverse elements long before the first episode dropped, another situation had been brewing in the two-year gap.

According to series creator Raye Rodriguez, the show did wrap up production in November 2019, which would have placed HSG as Crunchyroll Original’s first title to premiere had it released at its intended year. All that was left, according to Rodriguez, was for Crunchyroll to give the green light. Of course, that didn’t happen, with Crunchyroll Originals officially launching in early 2020. A full year went by and Crunchyroll was enjoying — depending on who you ask — some newfound publicity over their original programming, with new titles dropping almost seasonally. Yet among them, HSG was MIA, being pushed back again to 2021.

Given its critical reception when it did drop, your first reaction might be to chalk it up as Crunchyroll being aware that the show would be dead on arrival, with the company scaling back its promotion compared to its initial announcement two years earlier. While it’s evident that almost every Crunchyroll Original had some form of issue whether it was behind the scenes or the end product itself, the shows under Crunchyroll Studios Burbank are a particular sticking point for all involved.

In late 2018, aspiring animation creator Sara Eissa took to Twitter to outline her frustrations with an unspecified company, alleging bias against shows with diversity as a selling point while pitching their story to them. Though the company is never named directly, it’s been heavily implied to be Crunchyroll, with the company’s representatives noting they were now actively avoiding seeking projects with diversity given that their last one failed after they released a trailer highlighting the creators and “diversity” instead of showing actual footage.

Onyx Equinox creator Sofia Alexander made similar remarks, noting creators had no control over how their stories are portrayed, presented, or marketed. Instead of letting shows speak for themselves, Crunchyroll opted to reframe them to earn potential brownie points to bolster their own branding at the cost of their shows and their creator’s expense. If things couldn’t get any uglier, both Alexander and Rodriguez revealed one smaller detail that puts things into perspective.

During the promotion of HSG in 2018, Margeret Dean spoke to Digiday about Crunchyroll Originals, noting how these projects were being funded (emphasis mine):

“With ‘Crunchyroll Originals,’ the shows will be entirely funded by Ellation with budgets in the same range as what anime shows typically cost, Dean said. These original series also won’t come at the expense of shows co-funded, co-produced or licensed by Crunchyroll, which the company will continue to do.”

Later that year while speaking about the studio, she added “our budgets are on par with everyone else. We don’t have Simpsons or primetime budgets, but I’d say we’re in the Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network range. We’re pretty competitive.” In the aftermath of a long and tumultuous period of radio silence and shuffling of hands by Crunchyroll, Rodriguez would once again take to Twitter this year, revealing that HSG was under budgeted, non-union and had the staff scrambling to the finish line with the limited resources on hand.

Alexander would corroborate Rodriguez’s comments that same day, chiming in that their budget was “near 1/3 of a lot of western shows” and had pushed to unionize at the risk of leaving altogether. Onyx Equinox, despite being handled by the same team as HSG, had the fortunate advantage of learning from the former’s missteps, but still being kneecapped with many of the same limitations carrying over from the previous project.

Given that everyone’s preconceptions about these shows and Crunchyroll Originals are solidified at this point, I’m not interested in debating what a hypothetical increase in budget could or could not fix. Having just wrapped up my review of the first half of Lucifer and the Biscuit Hammer, sometimes you just have to accept that you can’t buy your way into a better story. As I’m sure as some of you can attest in today’s environment of blockbuster entertainment, there is no winning formula that determines whether you become a smashing success or a forgotten flop — and that’s before we get into critique.

A lot of people will no doubt focus on the results and move to shift the blame to the studios, but that’s missing the bigger picture. It was Crunchyroll who pushed for diversity only to renege at the first sign of trouble, choosing to reward the worst of its fandom and letting its partners and creators take the heat instead of standing by them. It was them who exclusively held the financial and promotional keys, choosing what got top billing and what needed to quietly “disappear.” And instead of taking responsibility for their failed ambitions or taking a long hard look at their plan, the company doubled down, choosing to shift the blame upwards because “diversity doesn’t sell.”

Before we get into the last section of 2019, I suppose we should briefly wrap up here with Adult Swim. Best known in the west as the adult block of Cartoon Network and host of the legendary anime block Toonami, the company has had an interesting turn of events in the wake of Crunchyroll and Funimation’s merger and its own parent company, Warner Bros. Discovery, who is currently slashing much of its animation departments.

With Fena: Pirate Princess, Blade Runner: Black Lotus, and Shenmue having long since been completed — with some varied results — and the last couple of projects, notably Uzamaki, still in the pipeline, it looks this will be the end of this relationship for the foreseeable future now that Sony has pulled back some of their other prominent shows off the block.

Having said that, there is one notable story worth mentioning — one that will become highly relevant entering 2022. At the recent 100% Union Power event, Anime News Network had the chance to speak with voice actors Kyle McCarley and David Errigo Jr. regarding the state of the dubbing industry. During the conversation, McCarley dropped some further details about one particular project prior to Crunchyroll’s merger:

Though McCarley would clarify he heard this anecdotally between similar joint productions involving Crunchyroll, it lines up with the company’s weak committal with its lack of clarity, communication and negligence over its own co-productions. But not all Crunchyroll Originals would meet the same swift fate, because the company had shifted priorities long before, attempting to save face by reshaping the narrative in their favor.

Rewarding Failure (Part Deux) — The Problem With Webtoon Adaptions

If you’ve read any of my previous work regarding Crunchyroll Originals, you’ve no doubt heard me discuss the concept of “hype culture” and how easily it can weaponized to justify, even overlook criticism in the interest of consumerism. To the uninitiated, I encapsulate this idea as “Rewarding Failure,” a system where a company takes advantage of their IP’s hype culture and blows it exponentially out of proportion in order to fully capitalize on its marketability and potential audience through overwhelming information.

If there was ever a poster child for Crunchyroll Originals, the original slate of webtoon adaptions — Tower of God, The God of High School and Noblesse — would become the identifying flagship IP of the then burgeoning animation lineup. From a business perspective, it made sense to bank on these properties. Three modestly well-known Korean webtoons with a built in audience of existing readers and the potential for growth in the much wider medium of animation, a partnership with several experienced studios (namely Sola Entertainment, who would play intermediary between Crunchyroll and other partners) and a huge marketing campaign courtesy of Crunchyroll, it’s no surprise that the company would find greater success with these — two out of three, give or take — than most of the shows discussed previously, at least from a branding perspective.

“But Dark Aether, you devilish fiend! People loved the manhwa turned anime adaptions even if they weren’t “faithful” adaptions! Just ask the dozens of positive on Crunchyroll right now! And the mostly positive aggregate scores on sites like MyAnimeList! Oh, and the half dozen or so popular Anime YouTubers who may or may not be sponsored by Crunchyroll and speak nothing but the truth! Surely, they can’t ALL be wrong?”

Well, my eagle-eyed friend, that’s just it. The sheer quantity of coverage and outlets sinking time and energy on these all coalescing at just the right time. When everyone has an opinion, it’s the loudest voices in the room that have the strongest chances of sticking out.

Critically speaking is a different matter, one that I’ve discussed in detail on this site (poor pacing, badly written characters, a lack of narrative payoff), so I won’t bother reiterating on those subjects. Aside from having a set of advantages other originals lacked including an existing fandom, experienced hands, marketing, there is plenty of evidence to suggest their overexposure had less to do with their positive and well-received aspects and more with who was telling the story.

Let’s start with Crunchyroll’s own marketing. In addition to additional coverage on social media and ads on their own platforms, the site published a number of features and articles aimed solely at promoting their new content with some very interesting language. For your convenience, I took the liberty of scanning the news section of Crunchyroll during 2020 and highlighted some of the more notable entries:

- Tower of God RULES And Fans Seem To Agree

- How Tower of God’s Top-Notch Atmosphere Makes the Show [Why atmosphere can be just as important as story]

- RECAP: The Latest The God of High School Succeeds Where Some Stories Fail

- FEATURE: Team Seoul is the Team 7 For A New Generation

- ESSAY: God of High School’s Yu Mira and the Power of No

- FEATURE: The Catchy Songs of Noblesse are the Perfect Excuse to get into K-Pop

This is a small sample of articles that ran from April to December of 2020. Notice a pattern? Without even factoring in the other recap articles, fan reaction pieces and promotional giveaways running during this period, almost every single one of these focuses squarely on the show’s superficial aspects to deemphasize the poor writing. While I can charitably chalk this up as “fluff pieces” and company mandates for its staff and freelance authors, it highlights Crunchyroll’s strategy of trying to win over fans through misdirection and repetition, greatly overrepresenting each show’s aesthetics over saying anything meaningful as reception and attention spans began to diminish in the months after.

Now let’s look at Crunchyroll’s most consistent third-party tools. First, they used popular streamers and personalities, paid sponsorships and a promotional giveaway or two to promote their originals. Next, they brought on celebrity guests to talk about their shows and generate hype. Not to imply that anyone was “paid off,” but the fact that a company like Crunchyroll has direct connections and influence over how certain media is portrayed reinforces the vicious cycle of advertisers, partnerships and inevitably consumers have on one another, leading to the same, boring, and predictable trends in determining what future projects get greenlit and which ones go off to die.

If you’re a paying customer, it also raises some genuine questions as to where all this money is headed towards instead of where it should be going and the lengths Crunchyroll would go to in order to keep their originals in the spotlight. In the case of Noblesse, it went into giving away pizza in order to promote the show, only to subsequently stop promoting it, for reasons that will become more apparent further down. Perhaps a miscalculation on their part, but aside from a few episode recaps, its only featured article came in December — to highlight the music. In 2021, they bought “a multi-episode anime series” from the WWE, a company with its own history of controversies, with still no mention of what became of this purchase as of this writing.

Even when the company wasn’t self-promoting or partnering up, it had no shortage of fans and people doing their work for them at the low cost of nothing. By far most damning piece of revisionism came from an article on CBR titled “Noblesse Is NOT a Great Webtoon Adaptation, but Still Worth Watching,” which brings me back to my original point at the start of this section.

Anime as a medium is generally thought of as visual media first, story telling second. We tend to judge with our eyes before opening our hearts and minds, which is why a lot of criticism today has a tendency to overemphasize spectacle and “budget” in place of good writing, or as the old cliché goes, “style over substance.” This is all subjective of course, but the biggest mistake I see committed to paper is mistaking the two as interchangeable, and when you throw objectivity out the window, then you start making shit up. “The animation is good. The music is good. Who needs narrative, character development and good writing when you’ve got atmosphere and cool stuff happening on screen?”

Before you answer, ask yourself “is it really enough?” What is the value of having a cast of characters without proper motivations, conflicts and challenges to overcome and get invested in? What is the weight of beautiful music and incredible animation without emotional stakes and profound moments to back it up? What is atmosphere without world-building or history and environments without anything worth preserving? You don’t have to answer or agree with me, but if you’re settling for less or constantly having to defend issues like the ones I’ve highlighted, if Crunchyroll thinks this is bare minimum these IP (and you) deserve, then is it really worth your time and attention?

Thus ends the legacy of Crunchyroll Originals, a stained monument of deception and bad faith built solely for the purposes of selling the company brand instead of producing great art. Unfortunately, the story doesn’t quite end here.

The problem with webtoon adaptions is a topic that’s been getting more traction lately following the announcement of a Solo Leveling anime to be released sometime in 2023, and while this is outside the scope of the main article, it’s worth briefly highlighting what Crunchyroll likely didn’t account for in their plans. In no particular order, underestimating what they were signing up for, putting out nearly three identical titles of the same genre back to back, and hardcore fans greatly “overhyping” their respective favorites to everyone’s detriment, as well as a general misunderstanding of the differences between manga and manhwa in their approach to storytelling.

With all that in mind, there is one more factor that would ultimately seal the fall of Crunchyroll Originals — competition.

Released in October of 2020, Jujutsu Kaisen was the breakout success of the year Crunchyroll had been envisioning for its originals. Featuring a better handling of its source material, story and characters, style and substance, and actual spooky, supernatural elements with devotion and care for its mysticism and humor, it should come as no surprise that the company shifted gears and went all in, making sure you knew the only place you could watch it was Crunchyroll at the time.

Of course, their newfound success would in itself become a curse (pun intended) in more ways than one. Aside from highlighting all the issues of the webtoon adaptions, this was right about the turning point for the company where they simply stopped promoting Crunchyroll Originals with the same level of fervor. Occasionally, the odd article was thrown in just to keep up appearances and the program would linger on into 2021, but most had finally moved on with the company’s own awards show that year seemingly confirming the changing shift from a business and a consumer point of view. Or as I like to put it:

“Okay, okay, you made your point! Sure, they told a few white lies, might have exaggerated the truth about their successes, spent money that probably should have gone elsewhere and may have done slightly more damage to their storyteller’s careers, properties and any potential adaptions of other webtoons. Crunchyroll Originals are dead. At least, I think they are. I don’t know anymore. Why does this matter now?

*laughs*

Here’s the fun part. Everything I highlighted above — all of the corporate sponsorships, paid advertisements and promotions, celebrity collaborations and negating bad press through the propaganda machine known as hype culture — is still being actively utilized as of this writing.

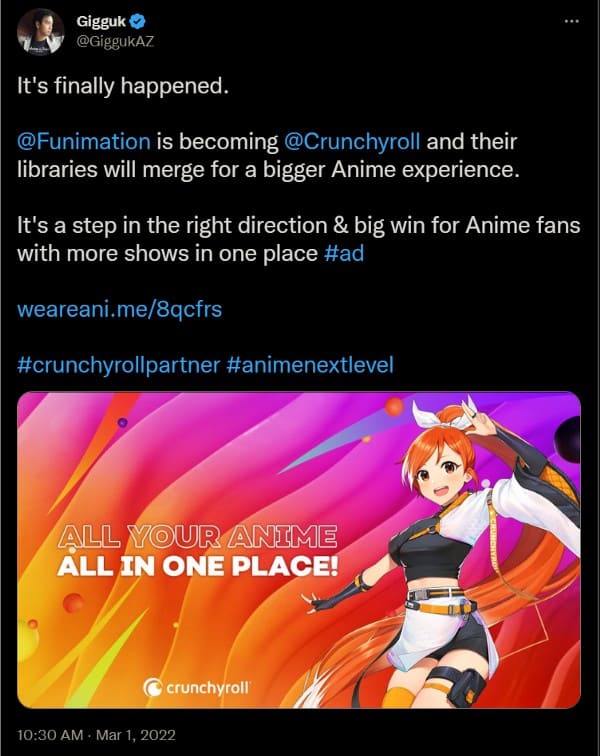

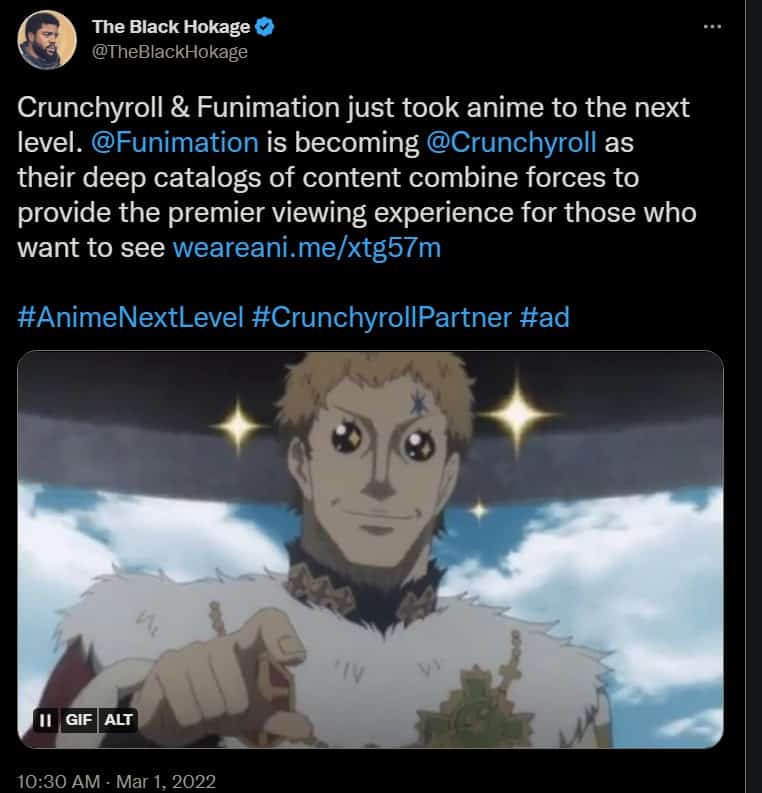

In 2022, they still rely on popular streamers and influencers to engage their potential audience and drive-up hype. The company still maintains a close relationship with celebrity guests, whether to talk anime to the company’s benefit or releasing exclusive merchandise to further build up their brand. And as for their favorite tactic of releasing their own press releases and news, they now had Funimation under their thumb talking up how “everything is fine” as their own social media presence would quietly shift over to Crunchyroll in the months that followed.

Because what better way to promote your upcoming merger and reposition yourself as the benevolent overlord looking out for the common folk than by rewriting the script and painting it as the people’s victory. After all, “fans win” is a much easier sell than telling customers that their freedom of choice is about to be severely reduced when you’re the biggest player in town. But we are not quite yet there because we still have one more year to cover! In 2021, Crunchyroll would see another dramatic change in ownership once again.

2021 — Sony Buys Crunchyroll

Back in 2018, one of the reasons the original Funimation/Crunchyroll partnership fell through was that Sony wanted to expand Funimation into international waters — something Crunchyroll had already done. Two years later, both companies were spending ridiculous amounts of money, whether it be broadcasting rights, co-productions or, in Crunchyroll’s case, spearheading its line of originals. In 2020, news started circulating that WarnerMedia and AT&T were looking for a potential buyer for Crunchyroll, and at the top of that list of buyers was none other than Sony.

Before we get into the details of the transaction, it’s worth highlighting how this deal came to be. In the United States, AT&T is best known as one of the most influential telecommunications companies, most notably providing phone, Internet and cable distribution. It’s a company with a long and detailed history (especially for you networking folks!), but all you need to know is after acquiring TimeWarner in 2016, AT&T’s venture into the entertainment business wasn’t panning out as they intended. Coupled with a heavy amount of debt accumulating since the 2010s and the company was well on its way into exiting their Hollywood ambitions.

On Sony’s end, we already know why they would want Crunchyroll — already owning the second largest anime company in Funimation, expansion into international markets, more influence over the anime industry and less competition — but for AT&T, it was a matter of reorganization and priorities. In 2021, AT&T CEO John Stankey announced it was selling WarnerMedia to Discovery, deciding that the company needed to return to its roots in telecommunications. During negotiations, AT&T reportedly asked for $1.5 billion, a number than even Sony balked at. Naturally, this was more than the company was expecting to get once the deal was finalized, even after shopping around.

Then there’s Crunchyroll, which despite reaching 3 million paid subscribers out of a registered 70 million, had its own demons it had yet to exorcise. In addition to failing to maintain and update its aging infrastructure, increasing the cost of their subscription without adding anything in return, losing out on licenses due to increased competition, and the disastrous rollout of Crunchyroll Originals, the most damning piece to its stained reputation would come in the form of its poor translator rates — a precursor to what was to continue post Sony’s acquisition. Adding in the ongoing and increasing costs of the anime industry and Crunchyroll’s own questionable investments at the time, it’s safe to assume that AT&T had more than enough incentive to sell it off as quickly as possible even if it was a way for them to clean up house.

On August 9th, 2021, Sony officially acquired Crunchyroll, becoming the largest distributor of anime combined with their previous acquisitions of Funimation and Aniplex. In a press release statement, Chairman, President and CEO of Sony Group Corporation Kenichiro Yoshida commented on the newly formed deal:

“We are very excited to welcome Crunchyroll to the Sony Group. Anime is a rapidly growing medium that enthralls and inspires emotion among audiences around the globe. The alignment of Crunchyroll and Funimation will enable us to get even closer to the creators and fans who are the heart of the anime community. We look forward to delivering even more outstanding entertainment that fills the world with emotion through anime.”

Though Sony is no stranger to anime, having worked in the industry years prior and aggressively strengthening its portfolio since 2015, many onlookers pondered about the future of the industry and what changes were in store now that the two largest anime streaming platforms now answered to the same parent. Unfortunately for all involved, those changes would manifest in some rather unpleasant ways.

2022 — In The End, It Was Never About The Art — Crunchyroll

A little over half a year later on March 1st, 2022, Crunchyroll and Funimation announced that the former rivals would unite under Crunchyroll’s banner beginning with the upcoming Spring anime season. Following this merger, concerns started to surface about Sony’s growing monopoly. As content and users shifted over to Crunchyroll, more changes would go into effect starting with subscriptions. For nearly eight months, stories began to break out as industry veterans and other insiders began to come forward, painting a very different picture about the San Francisco based distributor.

Reviewing my notes this year, I’ve organized these stories into three main categories, starting with:

The King is Dead. Long Live the King?

Not long after, the renewed Crunchyroll began to aggressively pull out its bag of advertorial tricks. On both organization’s sites, they touted the partnership as a victory for the community. “Anime Fans Win as Funimation Global Group Content Moves to Crunchyroll Starting Today” said Crunchyroll. “Funimation Global Group to Acquire Crunchyroll: Fans Win!” Funimation posted on its blog. As reported by The Canipa Effect on his video commenting on the merger, popular anime streamers and online personalities were even paid to simply say nice things about the upcoming merger to sell the public that “Hey, all your favorite anime is here now! Y’all like anime?”

For all the clever slogans and paid advertisements, even Crunchyroll couldn’t obscure the fact that the cost of operations has been steadily increasing among streaming platforms with virtually every major player passing the buck back to the consumer. In other words, it didn’t take long for it to implement sweeping changes, starting with its most popular option — the free tier.

With the upcoming spring 2022 season being primarily led by Crunchyroll, the company announced that moving forward, new content would be limited to the first three episodes as a trial run for potential customers. Those of you wanting to check out the highly anticipated Spy x Family or any future releases, for example, would be doing so now at a premium, which based on Crunchyroll’s registered users reported earlier, I imagine would be many of you reading this very article. Now to be fair, this was always going to be inevitable given the ever-rising costs of this economy, but as stated in the 2019 portion above, if you’re going to charge more, the level of service should match it as well — in theory.

To reiterate an earlier point, accessibility options, bug fixes and easier navigation between languages, all things that have been frequently requested — issues that should have been addressed by Crunchyroll three years ago, if not sooner when you decided to go solo. So, you’re telling me now under Sony, a multibillion-dollar conglomerate with the largest share of the anime market on the planet still doesn’t have a business plan for dealing with this when they bought them up one year earlier and just axed its other half without a viable solution in place?

Apparently so, because Crunchyroll itself confirmed as much with its time-tested formula of “eh, we’ll get to it eventually.” In an interview with Anime News Network, a company spokesman outlined some key details about the merger, including what users could expect in terms of what they were accustomed to. Closed captions like Funimation has been doing for several years? “We’re working on that.” Releases of home and uncut versions as is tradition? “We’re thinking about it. Maybe.” What about home and digital releases? How about fixes and improvements to the apps? Will translators continue to be paid competitively like they have under Funimation? Will there be layoffs?

Before we dig into that last part of that interview, there is one more relevant story to cover. On August 4th, Crunchyroll purchased the popular anime storefront Right Stuf. On the surface, the most notable change from the customer end is the removal of erotic content and “hentai,” which has been shifted to a new distributor in the form of the Ero Anime Store. Of course, I’m not here to kink shame! Though, I do find it ironic that the same company who famously didn’t bother to properly add appropriate content warnings to series like Goblin Slayer and the recent Skeleton Knight In Another World until after the fact is suddenly interested in being a “family friendly” type of company.

Then there are the layers of what this acquisition means down the road. CBR outlines the potential consequences of a Crunchyroll owned market now that Sony effectively controls both the distribution and physical markets of anime and manga. Too much power under one entity leads to less competition, effectively enabling Crunchyroll to do whatever it wants, distribute the titles it sees fits and explicitly remove content whether it be personal bias or potential rivals. Because most of their operations come out of North America, this would also diminish wages and make it harder to get a foot into the door with Crunchyroll being the primary means of obtaining employment in those areas.

The absorption of Funimation, the ever-growing lists of things Crunchyroll has been promising for several years now and failing to deliver, and Sony’s persistence in trying to dominate both the front and back ends of the anime market. Any way you slice it, the only remaining victor left is Crunchyroll — it just doesn’t have the same nice ring as “fans lost.”

The Battle to Unionize — Translators and Voice Actors Weigh In

From writers, to animators and actors, it’s no secret that the anime industry is an underpaid, undervalued and exploitative business being fueled by blood, sweat and tears. If you happened to watch any recent subbed anime on any platform recently, it’s easy to take for granted the convenience and relative ease it is to find the latest episode, completely subtitled and ready to go. Contrary to popular belief, subtitles don’t grow on trees and it’s not some byproduct of an advanced machine algorithm. Language is a complex system requiring an understanding of nuances, social awareness and general conversation etiquette, which goes doubly so if you find yourself writing character dialog one day. In simpler terms, how to write human.

The role of a good translator is more than simply translating from language to another, and in the art of storytelling, ensuring meaning and understanding isn’t lost in translation can make a world of difference from one audience to another. Which is all the more disheartening to hear that not much has changed for translators since I started writing about anime and getting an uncomfortable look at the industry’s underbelly. Prior to writing this piece, I didn’t realize was how deep it went, and at the forefront of repeated labor issues and questionable strong-arming is — you guessed it — Crunchyroll.

A quick web search for “Crunchyroll translator pay” pulls up a host of relevant sources, including Parts 1 and 2 of The Canipa Effect’s aptly named “It’s Impossible to Live as a Crunchyroll Translator” which provides a greater analysis on the topic at hand and where most of the information for this portion was collected. No matter where I searched though, the most consistent figure tossed around by those in the business puts the pay rate of a Crunchyroll Translator at about $80 an episode. Keep in mind, most of these folks are freelancers. That means no benefits, paid time off, insurance — the works. That’s also before accounting the amount of physical labor, the hours taken at a job with an irregular schedule where the work may not always be guaranteed, and the technical complexity of the content being translated.

Why $80 though? Turns out, it didn’t originate from Crunchyroll directly. In the mid-2000s, when fansubbers roamed the earth, anime had mostly been a word-of-mouth and passionate community with very little in the way of actual dollar figures being generated. As anime grew into popularity, so did business opportunities, and that is when a young Crunchyroll entered the fold, charging its users for what were essentially illegal translations of copyrighted material. Naturally, fansubbers weren’t happy, but that did little to deter them after receiving a sizeable $4 million investment in 2008.

With money in the bank, Crunchyroll went legit, and with a new business model came a need for a consistent workforce — a workforce which come in the form of a fansubber by the name of Ken Hoinsky and his company MX Media. If you want the full juicy story, I’d recommend watching Canipa’s first video if you have the time, but in 2010, Ken would sell his company to Crunchyroll before quietly making his disgraceful exit from the industry altogether. Given that MX Media had heavy involvement in Crunchyroll’s early simulcast days, it’s unsurprising the latter would take an interest in buying the former wholesale given their involvement in their formulative years and output.

The reality is far less rose-colored because MX Media found their silver bullet, continuously undercutting its competition to secure contracts with Crunchyroll, charging a meager $80 per episode. For comparison, most places would charge a couple hundred dollars for similar work. Ken would eventually vanish into obscurity, but the stigma remained as his company’s meager rates became Crunchyroll’s standard — a standard that persists even to this day. But even if Crunchyroll didn’t invent the standard, they damn well knew what they were doing, paying (to borrow Canipa’s words) “either less than half or less than a third of their competitor’s rates.”

Speaking of English based translations, now would be a great time to shift this over to the other side of the equation — dubbed content. As we noted earlier, Crunchyroll had mostly relied on outside studios for its dubs. Sony, for its part most likely got the idea that having two companies with similar services seemed redundant, and since their original plan was to expand Funimation while Crunchyroll had been reliant on third parties for its own dubs and home releases, someone thought “Hey, we own this company! And now we own this other company! Why are we still paying those other guys when we can do it all now right here!” And thus, the new/old Crunchyroll came into being with some sweeping changes on the horizon.

Within the cusp of the highly anticipated Spring 2022 season, the company fired its first round into the air and announced that it would be returning to in-person recording, two years after COVID took the world the storm and forced simulcasts to switch over to remote sessions. Now, I’ve seen a lot of different people weigh in on this quoting the pros (convenience, safety, opening up of pool talent) and cons (technical issues and limitations, the costs to transition to remote work). It’s a nuanced issue with several different aspects to consider and not a whole lot of definitive right and wrong answers, but after watching the video above, I think I can add a few additional bullet points to the conversation.

The first is Crunchyroll’s current commitment to solely producing most of its dubs in house. After previously utilizing several other studios, there was a notable drop in the number of talents being utilized outside Texas. ANN in the same article about the move back to in-person recording estimated that the outside talent during the spring 2022 season was “less than half of the previous season.”

While Crunchyroll denies telling its ADR directors to avoid hiring outside voices and ANN wasn’t able find someone willing to go on the record out of fear of retaliation, given that we’re now at least two seasons removed from that publication and a quick glance at some of the most prominent shows in that given season will tell you that almost all of their castings are based in Texas, with the exception of certain ongoing sequels and miscellaneous content, it can be reasonably deduced that this is the direction that Crunchyroll is headed into 2023.

The second point to consider is existing content and reprisal of previous roles. On March 8th, actress Reba Buhr posted a short tweet indicating she would not be working on anymore Crunchyroll shows because she “cannot afford to. If they raise wages, I’m all in.” For context, Buhr plays the lead character Myne in Ascendance of a Bookworm, which was on its 3rd season this year. Though the company did eventually come around in time for the premiere with Buhr confirming they “rose to the challenge and raised the rate,” other simuldubs were less fortunate.

On September 20th, actor Kyle McCarley posted a personal YouTube video indicating he would likely not be reprising his role as Shigeo “Mob” Kageyama in the upcoming third season of Mob Psycho 100 set to be released the following month. In an extensive interview with Kotaku, McCarley provided further details, including how he got in touch with Crunchyroll in order to potentially setup a meeting to discuss the issue in person after mysteriously not being asked to reprise his role even though the season had been announced back in January.

After a series of back-and-forth replies, Crunchyroll told McCarley their official position on the matter, stating that they would not commit to any union terms, refusing to discuss the issue further. And as if to firmly put their foot down, the company would later tell Kotaku that they were officially moving forward with the simuldub, stating that (emphasis mine):

“Crunchyroll is excited to bring fans worldwide the dub for the third season of Mob Psycho 100 III as a SimulDub, the same day-and-date as the Japanese broadcast. We’ll be producing the English dub at our Dallas production studios, and to accomplish this seamlessly per our production and casting guidelines, we will need to recast some roles. We’re excited for fans to enjoythe new voice talent and greatly thank any departing cast for their contributions to previous seasons.”

Back when Crunchyroll was utilizing third party studios, the first two seasons of Mob Psycho 100 were produced by Bang Zoom! Entertainment, located in California. In other words, most of the cast are not based in Texas. And with remote sessions off the table, well, I think you know where this is going. That same day, ADR director Chris Cason who worked on the previous two seasons confirmed he would also not be returning.

Within the course of 24 hours, a lead voice actor and an ADR director have departed with more recastings likely on the way. When the show’s simuldub finally did premiere, it would do so without cast information — a stunning departure for a company that likes to pride itself as an ally for the medium. Even worse when you consider that this is supposed to be the new face of English dubs after the company realigned everything under Crunchyroll Dubs. Add this with the company’s switch to in-person recordings, coupled by the fact that anime over the past two years had a pretty diverse talent pool from all over, and some of those shows just recently announced that new content was in the works, I have to ask is anyone safe? Only time will tell, but given recent events, things are not looking good.

Halftime!

My third and final point has to do with the medium as a whole and how its continued growth and success hasn’t really trickled down to those involved. 2022 alone saw the release of three of the biggest films of year — Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero, Jujutsu Kaisen 0 and One Piece Film Red — all of which set new records which is all the more impressive considering they didn’t have a traditional release and marketing campaign compared to Hollywood’s output. And when you factor in competition, how close they ranked to them, if not overtaking them, and the fact that all of these are animated foreign films, what’s there to say — people fucking love anime.

I wish I could say the feeling is mutual, but it isn’t. Any guesses how much a film like Jujutsu Kaisen 0 paid its actors? Go ahead, guess. What number did you arrive at? Was it…. $150? No, I don’t mean per hour. I didn’t mean $150,000 or $1500 either. I meant exactly $150, for the entire movie. According to sources who worked on the film, your average voice actor made about $150 — $300 at best. No royalties, no bonuses, nothing except the mere privilege of getting the ultimate bragging rights that you got to be part of an amazing film. Because who needs basic necessities like being able to buy groceries and make rent this month?

To put things into perspective, this film alone made almost $30 million at the US box office during its opening run. Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero made slightly above $20 million. One Piece Film Red made a little over $9.3 million in three days. Anime is bigger than it has ever been before, yet why are we still pretending like it’s still the mid-2000s? More importantly, if this has been going on for years now, why aren’t we talking about this more? Why does Crunchyroll continue to get a pass even after the medium has more than proven itself as a highly lucrative market?

In light of my research, I did come up with an answer. Needless to say, it’s not pretty.

What Are We Even Paying This Service For?!

Over the course of the year, there’s been a lot of discussion about fair wages in various sectors, notably the gaming industry, which is another can of worms that I suppose we should table for another day — this article is long enough as it is! One of the most frequent rebuttals whenever someone tries to engage this topic is “well, if the actors are getting paid better, why not the developers? The programmers? The artists? Musicians? Engineers? Writers?” The list goes on…

Applied to the anime industry and the same logic applies. “Why aren’t the animators making more?” Hell, just name any industry. Entertainment. Food service. Logistics and shipping. Folks, I’m going to let in you in on a little secret. I just need you to lend me your ear for a moment while I kneel down. You might want to write this down somewhere. Ready?

The sad reality is most people are not paid what they are worth. If an employer can get away with paying the bare minimum, they will because there is no financial incentive to pay what’s right. In fact, there is a whole field of study dedicated to the direct correlation between work performance and how much we earn. In other words, there is no single way to accurately predict that higher pay will necessarily equate to better performance, and in a system where employees are expected to compete with one another, undercutting your own value is one way to get your foot in the door. For the employee, it’s an entry level job at best, and for the employer, it’s plausible deniability until someone says otherwise.

Which is a damn shame because when you look at everything we’ve talked about — the translators, voice actors, creators, animators, etc. — given some of the conditions, limitations and time constraints most of these people are likely working under, the fact that most of these groups are able to maintain a certain level of quality without completely bucking under that pressure is nothing short of amazing. Simply put, they don’t get anywhere near the amount of credit they deserve, and it’s time we recognize it.

Now for one final hard truth — it’s time to stop waiting for Crunchyroll to do the right thing. I mean, they can if they want to, and I would certainly love it if they proved me wrong. It would certainly take less time for them to pick up the phone than what I spent on this article! But until they have incentive to change things, it’s easier for them to continue to sidestep the issue and talk about how great Mob Psycho 100 while ignoring and demeaning the people that made it great in the first place. It’s simpler for them to continue overcharging their customers with an inefficient app and outdated organization because where else are you going to get your anime fix from? (If I know one thing about anime fans, the FOMO is real!)

And it’s advantageous for them to continue mass marketing their latest shows and pray that the hype culture does its job to distract you from their other dealings because they’re counting on it. After all, how many outlets today are still talking about #JustAMeeting? How many fans do you think will remember the failure of Crunchyroll Originals when Tower of God season 2 or Solo Leveling arrives next year? Aside from people, what else does Crunchyroll consider expendable in the name of “art”? What will it take for us to finally say enough is enough?

In the end, it was never about the art. It was never about making anime better or celebrating cultural achievements. It wasn’t even about the profits and the number of users they could integrate into their ecosystem under the guise that it’s “for the fans.” Because when it comes down to it, Crunchyroll didn’t invent anime. It doesn’t create, innovate, contribute, improve or elevate the medium and the individuals directly responsible for its success. All they did was learn to reuse and recycle someone else’s work, put their logo on it and take the credit.

Come to think of it, I guess that’s the real story of Crunchyroll, an illegal pirating site turned legit that’s single claim to fame is that they beat out their competition in the gold rush that became the anime industry. They just happen to run most of it now.

But that’s all in the past now. After all, it’s just a brand.

What Now? (Final Thoughts)

Folks, I gotta be honest with you, this wasn’t easy to write. I debated several times publishing this at all. I wanted to quit halfway through, sacrificing far too many weekends and a good chunk of whatever free holiday time I had in November. Honestly, I wish had something nicer to end on, that things will be better moving forward.

As I arrived at this point, I had to remind myself why I choose to do this in the first place. Sure, there was several opportunities to turn back, and it is not like I didn’t have at least three open projects that I’ve neglected over the last three months. Yet, something compelled me to keep going. Call it writer’s pride or a stroke of madness, but I couldn’t leave this story half finished, even at my own personal and professional expense.

I had originally planned to share this for another article I had in mind, but then I saw something incredible happen. For the first time since I’ve started writing, I saw people come together to celebrate the fine folks who belong to this community. Across several platforms and social media, I saw journalists, even friends take matters into their own hands, putting themselves on the line against powerful corporations or simply taking a stand. For a moment, everything became clear to me. United at last, united as one.

Without further delay, I knew I had a story to tell. Not strictly mine of course, but for those without a voice. Though I don’t know who will read this and I doubt we will ever meet, I just want to say you’re not alone. Sure, it won’t be easy — the things worth fighting for rarely are — and there will be others who simply use the opportunity to further their ambitions. But then there will be those who take a stand, take the higher ground when the going gets tough and show bravery in the face of adversity. Most importantly, they will share your story.

Here’s my final task for you dear reader. Whatever you do with this information, however you take this story, do not stand idle. If you see something, say something. Whether you choose to boycott or keep your subscription, do so with the right intentions — I can assure you they have been reading your comments! Continue to follow the work of respected journalists and reliable sources, listen to insiders and, most of all, share their stories. After all, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing,” and our work has only begun.

Before I take my leave, I’d like to thank the community, my close associates and friends who encouraged me to pursue this story, the fine folks at Anime News Network for continuing to follow this story so closely, The Canipa Effect and The Cartoon Cipher who’s previous work has been invaluable during this endeavor, Doctorkev for being such an awesome person and the main inspiration for even considering doing this piece, and most of all, you my dear reader for making this all possible. Until next time, this is Dark Aether reminding you once again that I’m not dead yet.

For a complete list of resources and material pulled for this article, click here.

Resources — In The End, Crunchyroll Has Always Been A Brand

Oh, it’s you. Didn’t see you there! To be honest, I didn’t think anyone would click on this. If you’re coming from this…medium.com