Those of you who follow my work know I’m quite fond of dark subject matter, taking an interest in just about anything that tackles the strange, psychological and hidden worlds of the human psyche. Despite now entering what will now be my third article tackling difficult subjects, it may surprise you to know I take no pleasure in how closely some of these stories resemble my own real-world experiences. As you can imagine, it can make it difficult to simply sit down, unplug with a piece of entertainment and feel “normal.” Truth is I’m envious because I’ll never be able to engage with certain media the way that most people will.

That being said, one of my absolute delights on this platform is being able to share those experiences and highlight teachable moments through my love of fiction. When done correctly and with respect to the subject matter, it can open the conversation to a broader audience that may otherwise not have that exposure. I was reminded of this earlier this year in the excellent Kotaro Lives Alone.

For those unfamiliar, the show revolves around Kotaro Satо̄, an odd child that models himself after a cartoon samurai right down to his speech and mannerisms. He introduces himself to his neighbors who quickly get involved in Kotaro’s life. It’s a fascinating work that has what I consider to be one of the most realistic portrayals of inner trauma and how victims — notably children — process abuse. Throughout the series, we see Kotaro develop coping mechanisms, deny or downplay their emotions, or simply fail to recognize that they are victims of abuse by over-rationalizing or misremembering details.

The following article contains discussion of abuse, suicide and spoilers for the first 12 episodes of Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer.

You may be wondering what this has to do with Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer, which is what I suspect the reason you clicked on this article. Written and illustrated by Satoshi Mizukami, it’s a fantasy comedy adventure that also takes place in a modern setting except with knights, golems, and dark wizards. At first glance, the two stories couldn’t be anymore different with the former being a slice of life comedy in a more grounded environment and the latter leaning closer to shonen-like elements.

When it was announced that Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer would receive an anime adaptation, anticipation was at an all-time high both internally at AniTAY and pretty much everywhere that had some proximity to Mizukami’s body of work. A cult favorite from a distinguished author having already made a name for himself in both manga and anime, a decent word-of-mouth from the community and an unorthodox premise that very much screams a brand of “weird,” all the stars seemed to align.

But then the first trailer dropped and suddenly excitement turned to dread. Produced by Naz Studio (Hamatora Season 1, ID: Invaded), directed by Nobuaki Nakanishi, and cowritten by Yūichirō Momose and Mizukami himself, this unusual crossing of talent following a lackluster reveal didn’t exactly spell confidence in the minds of onlookers. “Okay, it’s a little rough, but let’s not jump to conclusions. They brought the author on board; it could still turn out okay.”

(Deep breaths)

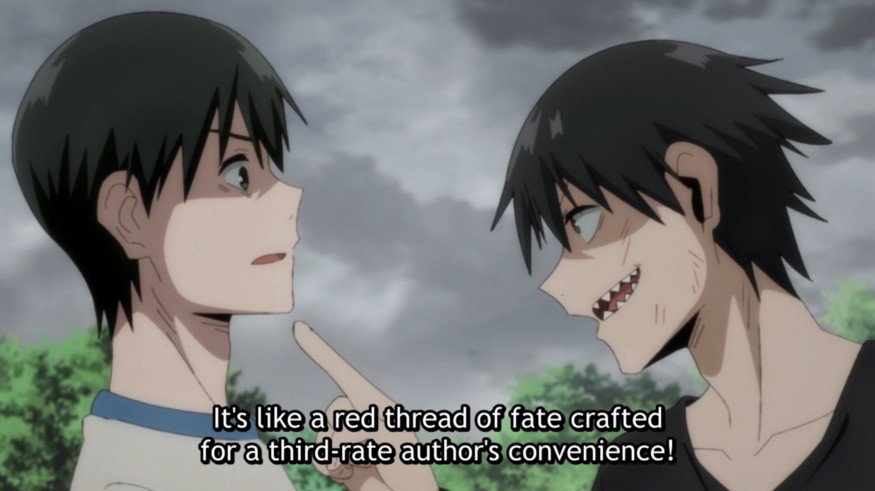

Let’s not beat around the bush; it’s an ugly show, and no amount of grandstanding or blind fandom is going to change the situation that this show found itself under. For now, let’s put that aside until it becomes relevant. This being my first exposure to the series, a lot of the discussion online has revolved around the show’s writing and Mizukami’s unique perspective on dialogue and storytelling. While it’s clear that certain liberties were taken in adapting this story, much of the focus has been squarely centered on how much of the story’s original intent has been preserved and how closely the characters take after their predecessors. “Because of how beloved Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer is. Because of how credited the author is.”

“Because of how good the writing is.”

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with having prior knowledge about a work as that in itself can provide a different perspective. But as I sat down to write this introduction and the synopsis below, I paused wondering “what exactly is Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer?” Now that we’ve reached the halfway point, I think I can answer that. Before our planet meets its own impending doom, let’s take a closer look.

Wishing for Destruction

Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer — or L&TBH from this point on — begins as college student Yuuhi Amamiya awakes to find a talking lizard in his bedroom. The lizard, Sir Noi Crezant, foretells a prophecy of doom involving an all-powerful wizard named Animus, an orbital space hammer hovering above earth and a gathering of a princess and her royal Beast Knights who must rise to the challenge, defeat Animus and save the planet from annihilation. Revealing Yuuhi has been selected to be the Lizard Knight, the skeptical young adult… chucks him out the window.

Eventually, he comes around when a stone golem comes knocking, but as the golem overwhelms him, his neighbor and the foretold princess, Samidare Asahina, arrives on the scene and obliterates it. Sensing a kindred spirit, Samidare proposes a secret alliance between the knight and princess: assist in defeating Animus and stop the Biscuit Hammer — so that she may destroy the world! Swearing loyalty to the princess, an unholy pact is formed and the countdown to destruction begins.

Right off the bat, we’re given a lot to swallow within the course of 23 minutes — a jaded protagonist refusing to accept his predetermined destiny, some odd ball humor with a casual gust of perversion and slapstick violence, and to top it all off, a doomsday scenario where the heroes aren’t the most altruistic people on the surface. It’s a lot to take in, yet the show wastes little time jumping into the next plot point. (This will be a recurring theme.)

Following the events of the first golem incident, more background is given into Yuuhi’s past. After losing both of his parents, his abusive grandfather takes him in, instilling his distrustful nature onto him. Suffering a bit of PTSD after being chained to a shed, he begins hallucinating chains. But after spending some time with Samidare — episode 2 I might add — she convinces him to go see his grandfather and get this cleared up.

(An abused child going to see their tormentor. Hmm, I wonder how this will go?)

Anyhow, Yuuhi goes to see his grandfather, who wouldn’t you know it is on his death bed and wants to break peace with his grandson. Yuuhi, as expected, calls out his bullshit, vowing never to forgive him. Oh, and Samidare promises to make out with him during one of his dream sequences which will thankfully never be explained because another golem is out hunting him. Yuuhi, in his one moment of quick thinking manages to get the golem to jump off a cliff, smashing itself under its own weight.

Then we go back to the hospital and things have turned for the worse for grandpa. It’s at this point where Noi brings up if Yuuhi accepts his contract and officially becomes a Beast Knight, he gets a free wish which he can use to save grandpa if he so chooses. After pleading with Yuuhi to let the past go, he reluctantly accepts and saves him, albeit refusing to forgive his past transgressions. For those still keeping score, that was episode 3.

To summarize this chain of events, Yuuhi is strung along by Samidare and Noi, forced to confront his abusive grandfather, took five minutes from his busy schedule to verbally kick a man down, fought a golem and had just enough time to accept a title he didn’t want, plus save his grandfather in the nick of time. A man who — from Yuuhi’s own words — deserved what was coming to him. Yet, everything works out in the end, grandpa didn’t die, Yuuhi got to make out with his crush in his dream, none of this gets referenced again and everyone lives happily ever after until the next arc.

“What did this actually resolve?”

Now, I’ve heard both arguments to this conclusion. On one hand, it serves to flesh out Yuuhi’s background beyond a blank nihilist wishing for destruction in order to get the audience to empathize with him. In other words, “the good kid” argument. On the other, it could be interpreted as an act of spite towards his grandfather, and by extension, the world as he resolves to aid in Samidare’s quest. The problem with both of these arguments is that the script doesn’t really support either of these theories with any definitive statement.

The relationship between Victim and Abuser isn’t established (exposition)

For starters, nothing about the grandfather, past or present, is elevatored on enough for the audience to establish him as a person. Beyond exposition and the one line of dialog from grandpa about not trusting others, we don’t get to meet him as the abusive guardian. As a dying man, we don’t get to see his character development or how his new lease on life came to be other than he’s a nice person now. We as the audience aren’t given enough detail about the relationship between victim and abuser, how they impacted one another, or how the resolution progresses them as individuals.

The resolution was achieved through manipulation of the victim

Going back to the sequence events, this is entire arc is brought on by Yuuhi’s fear of chains, which highlights a bigger issue with L&TBH’s idea of character progression. At the beginning of the arc, it’s Samidare that insists Yuuhi visit his grandfather to get over his PTSD. During the golem fight, he hallucinates Samidare who bargains a kiss should he survive. Towards the conclusion, it’s Noi who pleads with Yuuhi to accept the contract and save his grandfather with a wish despite still visibly reluctant to do so because he still hates his guts and doesn’t want to be burdened with the contract.

Are you seeing the pattern?

From beginning to end, almost every action taken by the protagonist is a result of another character’s persistence, often against his wishes if not flat-out bribery. This isn’t the worst case of protagonist inaction I’ve seen, but it certainly isn’t endearing either when your lead’s only contributions to their story is yelling at their abuser and reaffirming at every opportunity that they still intend to nuke the planet. Speaking of which:

The outcome has no lasting impact on the victim and returns to the status quo

One of the biggest issues I see in the depiction of abuse victims in modern day media is the overemphasis on the trauma itself rather than the victim. Remember, it’s not the ordeal that defines us, but rather how we overcome it so that we may become whole again and self-actualize. Finding the will to live and embrace freedom achieved by helping others in need. Abandoning toxic relationships and establishing new ones or strengthening existing bonds. Or my personal favorite, slowly recognizing the difference between parental love and abuse without internalizing the behavior of the latter.

Let’s revisit Kotaro Lives Alone. At four years old, Kotaro is characterized at the vulnerable stage of internalizing the actions of his abusers as normal. When pressed further about it by his concerned neighbors, his coping mechanisms kick in, going so far as to take the blame at the risk of “being left alone” again. But as they watch over him and uncover more about his past, they intervene, reminding him that we aren’t responsible for the actions of our tormentors and that the self-harm we inflict only deepens the wounds and the people we care about. How does it accomplish this? A short and simple reminder — “it’s not your fault.”

Okay, I might be projecting a bit, but the question remains. Or rather, how does this characterize Yuuhi further so that we as an audience understand his motivations?

In episode 1, we are introduced to Yuuhi the college student skeptical of the fantasy tale he’s being told. Episode 2 and 3 establishes his childhood trauma, which would explain his distrust of people, only to be walk backed in every other episode. We see him attend class, eat meals with company, and casually chat with the other knights as they are introduced. At one point, we even see him hit up the local bar and go on a date with Samidare clearly enjoying himself while simultaneously being told by almost every character about how important it is to enjoy the moment. “We adults smile to show how fun being an adult is and make kids jealous of us!” as one character remarks. For all the drama of his abuse of the previous arc and his willingness to doom the planet, the former is cleared up almost immediately while the latter is barely presented as a facet of his character.

The relationship between Yuuhi and grandpa could have been a compelling story to better identify why a seemingly ordinary man would suddenly want to become a harbinger of doom. Even if we can’t sympathize with his actions, it could have at least pivoted towards something human — revenge, pain, psychological damage or mental stress, literally anything resembling emotion. The aftermath could have been used to further characterize his isolation, his strained relationship with his grandfather and how it may influence his relationship with his soon to be comrades/enemies as the main story begins. It could have demonstrated his resolve to either move past his ordeal and do something productive or be consumed by his emotions and descend into true villainy.

I guess at the end of it, I simply don’t understand what this character is supposed to be. More frustrating than that, there’s a brief outline of what could have been. Instead, we’re treated to three whole episodes of exposition, poorly explained or lack of motivations and a protagonist who simply walks out neither a changed man or a compelling anti-hero. Why?

Because Yuuhi didn’t learn a damn thing.

But don’t just take my word for it. Ask its lead heroine.

My Little Lucifer

After the hospital visit and the awkward dream that neither of its main leads seem to recall the details (yes, this is a real thing!), another knight pays them a visit. Enter Shinonome Hangetsu, the dog knight and self-proclaimed hero of justice! To the source’s credit, Hangetsu ends up being one of the show’s more likable characters — you know, not down with the whole world ending. Yeah, I know, low bar, but progress nonetheless! He meets Hisame Asahina and falls head over heels for the older sister. We get a little more backstory about the Asahina household over some drinks, notably the absent father and Samidare’s mysterious illness as a child being cured without explanation.

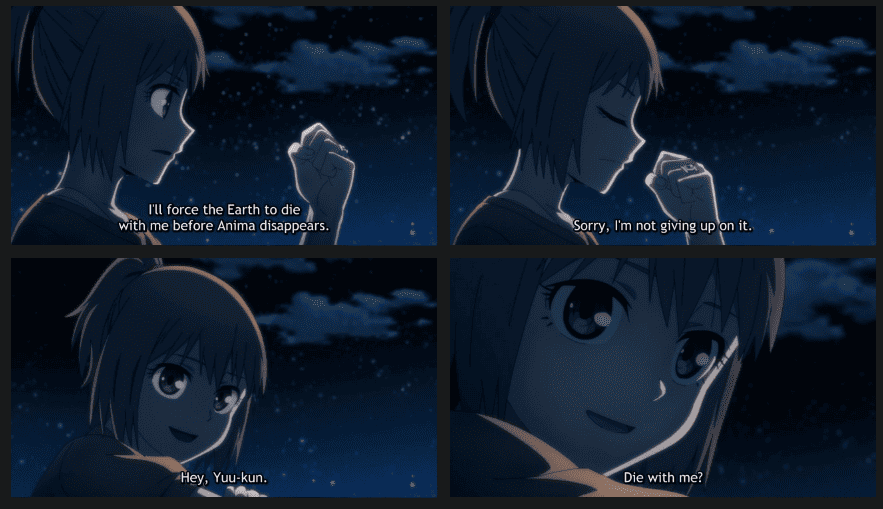

Yuuhi and Samidare speak privately and then the worst conversation in L&TBH happens. As luck would have it, Samidare was able to make a recovery through the powers of Anima, an unidentified being that for now explains how she became the princess. But once the threat of the hammer has been dealt with, her life will come to an end as Anima’s presence fades. It’s a moment of reflection turned sinister when she turns to her loyal confidant and asks:

Before I continue, let’s step back momentarily. Up until this point, Samidare has been playing the wildcard, simultaneously positioned as the main heroine, the dominant fighter of the team, a support pillar for Yuuhi and a double agent with her own agenda. While they subvert expectations by adding an unpredictable layer to the story, the problem is all four of these representations ultimately serve to fit the last one, which I’ll call “Lucifer.”

In the show’s opening moments, we are first introduced to Lucifer when Samidare intentionally jumps off the school roof, forcing Yuuhi to take action before revealing her true intentions and gaining his favor. The next time she reappears is in their shared dream where she once again states her intentions, this time offering a physical reward in addition to moving forward with their ultimate goal. Even when not present, Samidare’s motivations to fight the golems and relationship to Yuuhi is purely out of circumstance at best, but manipulative to self-serving on both sides. This is given more credence the moment Yuuhi opens his mouth and says:

Looking at Mizukami’s history and his follow up stories — the manga Spirit Circle and the anime original Planet With — something that always gets brought up is his subversive writing and quirky humor. I’m not opposed to throwing a little comedy to lighten the mood, especially coming off a heavy moment to catch a breather. But when your two main characters talk about physical abuse and terminal illness while spouting dialogue about killing themselves only after they’ve ended the world while the scene treats it as a completely normal thing to do, it’s not endearing — it’s horrifying. And if the counterargument is that it’s just a joke, then it doesn’t speak well about the author or how he views victims of trauma given he’s credited in the script.

Samidare is presented as another of Yuuhi’s classmate chums, a magical princess, a devil, and now a victim of fate that the show desperately wants us to empathize with. Like Yuuhi, it’s supposed to be portrayed as tragic, yet every other moment until this point has been Samidare as the spunky next-door neighbor or the seductive temptress who is more than willing to drag her pawn knight with her to the grave to satisfy her own chaotic tendencies. It’s this character inconsistency that makes it difficult to get a read on what L&TBH’s wants its heroine to be.

This is further evident in episode 10 when Animus reappears after the Beast Knights assemble for a beach retreat/training session and Animus reappears, whisking Samidare and Yuuhi away for a brief chat. It is revealed that Samidare is in fact Anima (note: episode 12 reveals she’s hosting her spirit), who gained her powers from her twin Animus and has been the mastermind, orchestrating a false narrative about magical knights and princesses in a diabolical game that has been seemingly unending. To quote Animus directly “she’s using human lives as pawns.”

It’d be a cool plot twist if this hadn’t been the same character we’ve been following since episode 1. We’ve known for a while that Samidare’s goal is in direct opposition to the knights. We knew that she had been withholding important information from the knights, including Yuuhi. So let me get this straight: the big reveal that L&TBH has been building up to for 10 episodes is that Samidare is… Samidare?!

Not that it matters because in episode 11, our heroes return home when Samidare’s mother pays them a surprise visit and Samidare switches to full spoiled brat mode. Normally, I would welcome a little family drama, but as we previously experienced with Yuuhi’s arc, L&TBH only seems concerned with tackling these issues on a surface layer. Funnily enough, most of the details come from Hisami, a character who has barely had a presence only now to be utilized to quickly explain how their mother left to France in search of a cure for Samidare only to ruminate about how distant their relationship has become. I’ll admit, that was pretty clever of the show to acknowledge how little their sibling bond has come up. Good job!

Then the two sisters have a private chat, Hisami with her god slap knocks the gremlin out of Samidare, and Yuuhi gets to play white knight by telling her that he’ll stand by her side no matter what — like he’s been doing for the past 11 episodes. Samidare gets to say goodbye to mom and for kicks, the show throws another “You’ve changed [insert false character development]” at Yuuhi by having him call his grandpa — you know, the one he would never forgive and had no reason to because they’re still going to destroy the fucking planet.

None of this is bad inherently, but when it comes down to it, all of the clever writing tricks and mental gymnastics can’t hide what is inheritably a suicide mission disguised as an action-adventure comedy. Perhaps some will read that as being uncharitable, so before reading the next section, allow me to pose a follow up question to my initial thesis: What kind of story is L&TBH trying to be?

Let Sleeping Dogs Lie

Earlier, I noted L&TBH’s inconsistency regarding Yuuhi’s personality, motivations and lack of agency in the story. It seems the narrative also agrees with me because episode 4 takes a pivotal turn for the remaining runtime. After our heroes’ embarrassingly shallow conversation about death, Hangetsu confronts Yuuhi who correctly deduces that he and the princess have not been forthcoming about their motives. Instead of doing anything, however, he lets him ago deciding it would be best to watch closely. You could have done that without telling him! Not that it matters because another golem shows up to conveniently clean up this plot hole for our heroes to best. Unfortunately, the golem proves to be too much for them to handle as it takes aim at Yuuhi.

Like a shopping cart slowly rolling across an empty parking lot, Hangetsu pushes Yuuhi aside to be completely pulverized by the rock monster. Jokes aside, this is the moment L&TBH decides that Yuuji gives a shit about something other than himself (or Samidare) by martyring Hangetsu. The same Hangetsu who offered him training which he immediately declined. The heroic knight of justice who is clearly a potential threat and directly opposed to your goals. The same guy who quite literally told you he was on to you and all you could do was wave your hands and play dumb.

Over the course of the following episodes, the show goes to great lengths to portray Yuuhi as a guilt-ridden survivor, frustrated by his lack of strength and how deeply Hangetsu’s death affected him. He meets more knights, begins to take the job seriously and train more vigorously — all of which should, in theory, be a breakthrough moment. But once again, L&TBH gets in the way of its own progress, introducing more characters than it knows what to do with and reiterating on its leads worst qualities. At no point does Yuuhi second guess or question what he’s involving himself with, instead doubling down on Samidare’s ploy. When given the option by Lucifer to turn back, admitting she expects Yuuhi to get cold feet, he repeats his pledge to see her plan to the end. In the episode where Animus reveals the knights’ story to be a ruse, he barely acknowledges it.

Throughout its runtime, L&TBH reiterates on the subject of growing up, constantly referencing it through similar phrasing. “Being an adult is fun. Children grow up by imitating adults. You’ve changed Yuuhi.” It even takes it a step further having Yuuhi unconsciously take up Hangetsu’s personality. Yet for all the tutelage he provides to the less-than-experienced knights and the ability to seemingly have some empathy when presented with a horrific scenario, his loyalty to Samidare is never once criticized or challenged, even after another knight overhears them. His reaction to Hangetsu’s death only furthers his drive to Samidare’s ambition. His involvement to the secondary characters only extends as much as the show allows before quickly reminding us that he has a doomsday plan in his pocket.

L&TBH’s greatest sin, however, is the general lack of polish and disinterest when it comes to its own lore and world building. Early on, we’re given a glimpse into its rules of magic (holding field), monsters (the golems) and Beast Knights along with their animal counterparts. It’s just that for every weird or brief spark of creativity (Swordfish Knight?!), it immediately gets upended by the next plot point. One minute, a character dies and the next day a bunch of strangers show up at your doorstep and suddenly we’re having a beach episode. The conflict between Anima and Animus still hasn’t developed past sibling rivalry 12 episodes in. Your lead characters can’t decide what they want to be, casually shifting between normal and manic without any of the charm or charisma to back up either.

All the ideas in the world can’t elevate a flawed script into a compelling narrative with interesting characters, motivations and relationships when the writing doesn’t support its own thesis. Because at the end of the day, what does L&TBH believe? Taken seriously, L&TBH believes that years of abuse and trauma can be overcome by changing nothing. That people can grow up by imitating those around them while ignoring the nature and uniqueness of the individual. Their pain, their experiences, their growth, the things that fundamentally make us human reduced to a children’s fable — to confide in the adults without question because they always know best!

As a comedy adventure, L&TBH believes that its heroes will never have to face repercussions. They will never be forced to challenge or change their beliefs while continuing to receive love and support in one hand and literally playing God with the other as they decide the fate of the world. All of the glory without any of the difficulty or fairness among its participants. When you’re the game master arbitrarily deciding the rules, who’s going to stop you?

Perhaps most tragic of all, L&TBH believes that it’s a mature, adult story, subverting common shonen tropes, but then delivers an immature, childish tale about two selfish adults who would rather go off and play with allusions of grandeur than actually do something about it. Still, I’m not without heart. Despite my criticisms, I’ll grant this show one final courtesy — “It’s not your fault.”

At Least It Has Good Writing? (Final Thoughts)

In the weeks that followed, there’s been a lot of discussion and debate over how L&TBH could have avoided its fate. Perhaps a more experienced studio should have taken the helm. Maybe the committee could have allocated more time and resources. In another timeline, the script wouldn’t have had to make as many compromises and had a bit more oversight. I’ve been hearing a lot potential solutions to these problems, but regardless of who was in charge or who is accountable, there’s another discussion that has yet to take place.

I’ve never been a big fan of the style over substance argument, but let’s suppose for a moment that this show had a complete visual overhaul, a reasonable budget and schedule, maybe even a bit more flexibility with the story’s pacing to flesh out the details. Does that change the context of the story? Does it make it okay to continue to overlook its manipulative handling of abuse and suicide?

While there’s a strong argument to be made that a visual medium has the ability to elevate stories beyond mere print, it cannot recontextualize the fact that L&TBH is still at its core a story about ending things. It doesn’t change the fact that its two leads are devoted solely to themselves, rebelling through their genocidal plan while never being pressed on it. At best, L&TBH is a confusing thread of underexplained ideas and underdeveloped characters played off as brilliant and self-aware. At worst, it’s just plain boring, if not divorced from reality about real world victims and trauma.

Because once you’ve removed all the prestige, the production issues and our own expectations and assumptions, there’s a better answer that doesn’t require a hammer and nails — Lucifer and The Biscuit Hammer is a mess.

Lucifer and the Biscuit Hammer is streaming on Crunchyroll.

Dark Aether is a writer/contributor for TAY and AniTAY. You can check his main writings on Medium, archives at TAY2, or follow him on Twitter @TheGrimAether. Not Dead Yet.

Get involved!

Comments